The American electric power landscape in early 2026 is characterized by a fundamental shift in demand and the resulting need for grid stability. After decades of relatively stable electricity consumption, the industry is now facing a surge in load driven by the rapid expansion of artificial intelligence data centers, the reshoring of heavy manufacturing, and the increasing electrification of transportation and heating. This sudden growth has occurred alongside a structural shift away from coal and older natural gas plants toward intermittent renewable energy sources.

————————————————-

No time to read the full article? Listen to Vedeni Energy’s Deep Dive podcast at vedenienergy.podbean.com

————————————————-

While the initial wave of energy storage focused on short-term lithium-ion systems for frequency regulation and small peak shifts, the current era calls for a different strategic approach. Utility sector leaders and managers are now emphasizing long-duration energy storage, or LDES, as essential infrastructure to bridge multi-day renewable energy shortages and maintain grid resilience amid increasingly frequent extreme weather events. For middle managers and executives, shifting to multi-day storage signals more than a technological upgrade; it signifies a fundamental rethinking of asset management, financial risks, and regulatory strategies.

The Strategic Shift to Multi-Day Capacity

As the use of wind and solar power reaches record levels across North American regional transmission organizations, the limitations of the traditional four-hour battery have become a key management issue. Short-duration systems are very effective at providing ancillary services and shifting solar energy into the early evening hours. However, they lack the energy density and cost efficiency needed to keep the grid stable during long periods of low renewable energy output or during severe winter storms that can last several days.

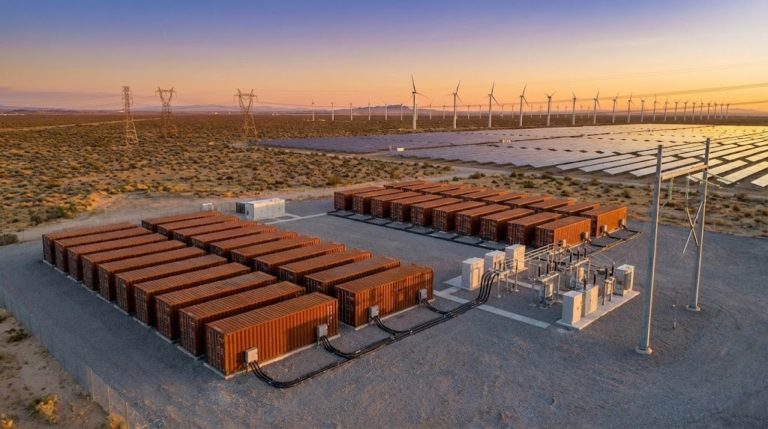

Management is now shifting its focus to systems that can provide 10, 24, or even 100 hours of continuous discharge. This move to multi-day storage is driven by the need for reliable resources to replace the retiring baseload thermal fleet. By investing in LDES, utilities can effectively stabilize their renewable portfolios, turning volatile wind and solar assets into dispatchable power sources that act more like traditional generators. This development is crucial for meeting the decarbonization mandates set by state legislatures and federal agencies while also supporting the power-intensive infrastructure of the AI boom.

Technological Diversification and the Rise of Iron-Air Solutions

The dominance of lithium-ion technology faces its first major challenge as utilities look for more specialized chemistries for long-duration use. While lithium remains the go-to for mobile and short-term stationary storage, its supply chain is highly concentrated and vulnerable to geopolitical instability. In response, management is shifting toward alternative battery technologies that use abundant, domestically sourced materials. Iron-air batteries have become a leading option for hundred-hour storage due to their use of low-cost iron, salt, and water.

These systems operate based on reversible oxidation—essentially rusting and un-rusting iron to store and release energy. From a management perspective, the appeal of iron-air and similar flow battery technologies lies in their safety and durability. Unlike lithium-ion systems, these newer chemistries are mostly non-flammable and do not experience the same degradation patterns, enabling a twenty-five-year operational lifespan that better matches traditional utility asset cycles. This technological diversification also serves as a strategic hedge against the tightening of foreign entity rules, which are increasingly restricting the use of components from certain international markets.

Economic Drivers and Energy Storage Investment Frameworks

The financial landscape for energy storage has matured considerably, shifting from pilot projects to multi-billion-dollar capital programs. Investment in energy storage now plays a key role in utility rate cases, supported by the long-term certainty provided by the Inflation Reduction Act’s tax credits. For senior management, the challenge is no longer just proving that storage works, but also optimizing the capital structure to handle the high upfront costs of LDES. These projects often require a larger initial investment than shorter-duration systems but deliver better levelized costs of storage over their lifetime by minimizing the need for frequent cell replacements.

Financial leaders are increasingly relying on “non-wires alternatives” as a key driver of storage deployment. By strategically placing long-duration assets at congested transmission network nodes, utilities can delay or avoid the need for large, unpopular, and costly new power lines. This strategy enables managers to expand their regulated asset base while actually reducing the overall cost of service for ratepayers, creating a persuasive story for both investors and regulators.

Regulatory Evolution and Grid Interconnection Management

The regulatory environment in 2026 has shifted from simple incentivization to a focus on implementation speed and structural reform. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission orders now require more comprehensive long-term transmission planning, which, for the first time, compels grid operators to consider energy storage as a solution for regional reliability explicitly. Meanwhile, managers continue to face the ongoing challenge of the interconnection queue backlog. With thousands of projects awaiting grid studies, leadership is exploring innovative solutions to bypass delays, such as co-locating LDES with existing fossil fuel sites or large industrial loads, such as data centers. This “behind-the-meter” strategy enables faster deployment and immediate reliability benefits for high-value customers. Additionally, state mandates are becoming more detailed; instead of merely setting a megawatt target for storage, many states now require a portion of that capacity to be long-duration. This evolution pushes management to engage more deeply with long-term integrated resource planning, moving beyond the two-year procurement cycle toward a decade-long strategic outlook.

Workforce Readiness and Operational Resilience

The technical complexity of managing a grid that depends heavily on long-duration storage demands a complete overhaul of traditional utility operations. Middle management currently faces a significant talent gap, needing to recruit and retain professionals who understand both the physical properties of electrochemical storage and the software required to optimize it. Modern LDES systems are integrated with advanced energy management platforms that utilize artificial intelligence to predict weather patterns and wholesale price fluctuations, making decisions within milliseconds about when to charge or discharge.

This requires a workforce comfortable with both data science and high-voltage engineering. Operational resilience also includes the physical and digital security of these assets. As storage becomes the backbone of grid reliability, it turns into a prime target for cyberattacks. Management must adopt zero-trust architectures and strengthened communication protocols to prevent these distributed assets from being compromised. This emphasis on cybersecurity is now an essential part of the procurement process for any new energy storage system.

Integrating Storage into the Broader Energy Ecosystem

The successful deployment of LDES cannot happen in isolation; it must be part of a coordinated strategy that includes virtual power plants, demand response, and nuclear life extensions. Managers are increasingly viewing the grid as an interconnected system in which large-scale LDES provides multi-day baseload support, while distributed resources—such as home batteries and electric vehicles—provide high-frequency response. This “layered” approach to storage enables utilities to maximize the efficiency of the entire system.

For example, during periods of high solar production, short-duration batteries can handle the immediate surplus, while LDES units store the longer-term excess for use over several days. This reduces the need for “curtailment,” or the waste of clean energy, because there is nowhere for it to go. For management, this means developing more advanced market participation strategies, as storage assets now have to navigate multiple revenue streams, including capacity payments, energy arbitrage, and ancillary services across different timescales.

Managing Public Perception and Community Impact

As energy storage facilities increase in size, they are increasingly facing the same “not in my backyard” challenges that have long affected transmission and wind projects. Middle managers are being assigned to engage communities more actively to explain the safety and necessity of these projects. The adoption of non-flammable LDES technologies, such as flow batteries or thermal storage, offers a significant benefit in this area, as they do not pose the same fire risk as earlier lithium-ion setups.

Furthermore, federal programs like the Justice40 initiative require utilities to ensure that a share of the benefits from new energy investments reach disadvantaged communities. Management is responding by locating storage projects where they can boost local resilience—such as at community cooling centers or hospitals—while also creating well-paying, long-term technical jobs. This emphasis on social license has become a crucial part of project development since local opposition can cause delays that significantly outweigh any technological or financial setbacks.

Environmental Impact and the Circular Economy

A key management priority in 2026 is ensuring that the energy transition does not trigger a new environmental crisis from battery waste. Although LDES systems generally use more abundant materials, they are physically much larger than short-duration systems, requiring a dedicated end-of-life recycling and material recovery strategy. Proactive leaders are integrating “circular economy” principles into their procurement contracts, requiring suppliers to take back systems at the end of their 25-year lifespan. This is not only about environmental responsibility but also strategic mineral security. By developing a solid recycling infrastructure today, utilities can ensure that the materials used in the current storage systems remain available for future use. This long-term perspective is vital for maintaining utilities’ “green” credentials and for fulfilling the increasingly strict environmental, social, and governance reporting standards of today’s financial markets.

Looking Ahead to the End of the Decade

The future of the U.S. electric power industry through the 2020s will depend on how effectively it can incorporate long-duration storage into its core functions. We are currently in a “liftoff” stage, where the initial wave of commercial-scale LDES projects demonstrates the technical and economic feasibility of multi-day storage. In the coming years, managers will focus on expanding these solutions to support the hundreds of gigawatts of capacity needed for a fully decarbonized grid. This will require ongoing technological innovation but, more importantly, a continued shift in regulatory approaches and financial models. Utilities that lead in securing long-duration capacity will be best equipped to handle the volatility of the new energy landscape, offering stable, reliable, and affordable power that can drive the next wave of American economic growth.

Conclusion

Long-duration energy storage has shifted from the outskirts of energy planning to its core. As the industry faces the dual challenges of unprecedented load increases and a swift move toward intermittent renewables, the ability to store energy for days at a time has become essential for grid stability. For leadership and management, this requires moving away from short-term focus and adopting a long-term strategic vision that includes technological diversity, financial innovation, and a reimagined workforce. By focusing on LDES today, the electric power industry is not only creating a more flexible grid but also laying the groundwork for a modern, electrified economy resilient to market swings and climate extremes. The road to 2030 and beyond is built with storage, and the choices made by today’s managers will shape the reliability and competitiveness of the U.S. power sector for decades.