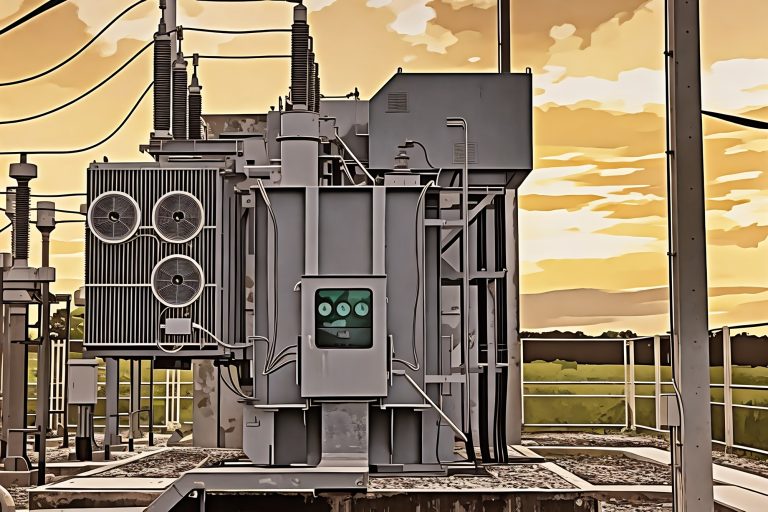

The United States electric power industry currently faces a precarious situation with unprecedented demand and long-standing supply vulnerabilities. For decades, the sector relied on efficiency, heavily dependent on globalized supply chains and just-in-time inventory strategies to keep costs for ratepayers low. However, this model has collapsed. As the industry progresses through the latter part of the 2020s, utility leaders are confronted with a “poly-crisis” characterized by geopolitical fragmentation, extreme weather events, and a surge in load demand driven by artificial intelligence data centers and widespread electrification. This strain has revealed significant weaknesses in sourcing critical infrastructure, especially high-voltage (HV) transformers and circuit breakers.

————————————————-

No time to read the full article? Listen to Vedeni Energy’s Deep Dive podcast at vedenienergy.podbean.com

————————————————-

The modern utility executive must now shift from a focus on cost optimization to one of resilience. Open global markets no longer assure the availability of essential grid components. Instead, it is limited by raw material shortages, protectionist trade policies, and a manufacturing sector that has struggled to keep up with the electrification of the economy. This change demands a fundamental rethink of how materials are sourced, stored, and managed. The era of seamless global supply chains is over; the era of “friend-shoring,” strategic inventory pooling, and domestic industrial policies has begun. This Energy Brief examines the current state of the utility supply chain, explores the strategic move toward sourcing from allied nations, and outlines the operational requirements for inventory management in a resource-limited world.

The Current State of the Chain: A Deficit of Critical Hardware

The defining feature of the current market is a significant gap between the timing of needs and the delivery process. Lead times for essential grid assets have grown well beyond historical norms, creating bottlenecks that could slow the energy transition. Industry data shows that procurement cycles for Large Power Transformers (LPTs) have increased from less than a year to now often surpassing 120 weeks. In some cases involving specialized units for renewable integration or high-voltage direct current (HVDC) transmission, utilities face lead times of nearly 4 years. This mismatch in timelines poses a serious threat to reliability, as the failure of just one critical asset could leave parts of the grid vulnerable for months or years while waiting for a replacement.

Several factors contribute to this deficit. First, the high demand volume. The rapid growth of data centers, driven by the generative AI boom, has created localized “hyper-load” areas that demand immediate grid reinforcement. At the same time, the broader push for economy-wide electrification—including electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure and building heating—has increased the baseline load growth projections nationwide. Utilities are trying to rebuild and expand the grid simultaneously, even as the existing transformers are nearing the end of their operational life.

Beneath the surge in demand lies a fragile supply chain for materials. The production of transformers heavily depends on grain-oriented electrical steel (GOES), a specialized alloy with high magnetic permeability. Global capacity for GOES has not kept pace with demand, and prices for the material have doubled in recent years. Additionally, copper, the other main raw material for grid infrastructure, has seen prices increase by over 70 percent since the beginning of the decade. A labor crisis worsens these material shortages. Manufacturing HV transformers requires specialized manual winding skills that cannot be easily automated. A “silver tsunami” of retirements among skilled tradespeople, combined with few new workers entering the heavy manufacturing sector, has limited original equipment manufacturers’ (OEMs) ability to expand production even when materials are available.

The Strategic Pivot: Friend-shoring and the Geopolitics of Procurement

In response to these vulnerabilities, utility leaders are fundamentally restructuring their procurement strategies. The concept of “friend-shoring”—limiting essential supply chains to politically allied nations—has shifted from theoretical economic policy to an operational necessity. The risks of relying on adversarial or non-aligned nations for critical infrastructure have become unacceptable. Geopolitical tensions, tariffs, and the threat of weaponized supply chain disruptions have prompted North American utilities to focus more on domestic sources. The strategy involves disengaging from high-risk regions and increasing reliance on trade partners with shared security interests and stable political environments, primarily Canada, Mexico, and the European Union.

This geopolitical realignment is not just a preference but a requirement for compliance. Federal scrutiny of the origin of grid components has increased, driven by cybersecurity concerns and the need to safeguard the bulk power system from foreign adversaries. Procurement officers now must trace their supply chains multiple tiers deep to ensure that sub-components and raw materials do not come from prohibited entities. However, this shift presents its own challenges. While friend-shoring reduces geopolitical risk, it also concentrates reliance on a smaller group of suppliers. Mexico, for example, has become a key hub for near-shored manufacturing, but capacity there is quickly filling up as nearly every major U.S. utility moves in the same direction at the same time.

The push for domestic energy manufacturing naturally follows this trend, heavily supported by recent federal policy frameworks. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) have offered significant incentives to bring clean energy component production back to the U.S. However, rebuilding a domestic industrial base for heavy electrical equipment is a multi-year, possibly multi-decade, effort. While new factories are announced, the time between breaking ground and reaching full capacity means domestic supply will likely stay tight for the near future. As a result, utilities must manage a transition period with a hybrid approach: prioritizing domestic sourcing when possible, using “friend-shored” capacity to meet volume needs, and carefully vetting any offshore components.

Utility Inventory Management Strategy: From Just-in-Time to Just-in-Case

The most immediate operational shift for utility management is the end of “just-in-time” inventory practices. For thirty years, the industry was rewarded for maintaining lean inventory, which freed up working capital and cut carrying costs. In today’s environment, lean inventory has become a liability. Not being able to access a spare transformer during a major failure poses reputational and financial risks that far exceed the cost of stockpiling idle assets. Utilities are now actively building strategic reserves, increasing their supplies of critical spares to prepare for potential supply disruptions.

This hoarding behavior, while logical for each firm, causes a tragedy of the commons that worsens the industry-wide shortage. To address this, proactive leaders are adopting inventory pooling strategies. The idea is simple: instead of every utility maintaining a spare for each voltage class and impedance, utilities form consortia that share a common pool of standardized assets. Organizations like Grid Assurance have led this approach, enabling members to subscribe to a shared inventory of essential transmission equipment. During a qualifying emergency, subscribers can access the pool, significantly reducing the time needed for replacements.

Successful inventory pooling requires a shift in engineering culture. Historically, utilities have prided themselves on custom engineering, designing transformers tailored to their specific legacy systems. This lack of standardization complicates pooling, as a transformer designed for Utility A might not fit Utility B’s substation. To make inventory management strategies effective at scale, engineering departments must adopt standardization. By establishing a limited set of specifications for new builds, utilities can develop interchangeable assets that can be shared across service areas. This operational flexibility is essential for supply chain resilience, which utilities need to survive the current shortage.

Critical Infrastructure Procurement: The New Rules of Engagement

The transactional nature of procurement is transforming into a partnership model. In a buyer’s market, utilities could use competitive bidding processes to lower prices. Today, in a seller’s market, OEMs have the advantage. To secure production slots, utilities are moving away from spot-market purchases in favor of long-term framework agreements (LTFAs). These involve committing to purchase volumes years in advance, effectively reserving factory capacity before projects are fully scoped. This demands a much closer integration between capital planning, engineering, and procurement teams. Supply chain officers can no longer wait for a final engineering design before placing an order; they must reserve the slot based on forecasted needs and finalize the technical details later.

Furthermore, procurement strategies must now consider raw material indexing. Due to the volatility of copper and electrical steel, OEMs are becoming less willing to commit to long-term fixed-price contracts. Utilities are having to include price escalation clauses linked to commodity indices to secure deals. This introduces a new layer of financial risk that must be managed through hedging strategies or regulatory mechanisms that allow recovery of variable capital costs.

The role of the procurement leader has been raised to a strategic level. They are no longer just purchasing agents but risk managers who must weigh the financial costs of long-term commitments against the operational risk of unavailability. They also need to actively manage supplier relationships, conducting regular audits and factory visits, not just to ensure quality but to verify that the supplier has secured their own sub-tier materials. Visibility of the HV transformer supply chain must extend all the way to the mine and steel mill.

Navigating the Domestic Manufacturing Landscape

The push for domestic manufacturing offers a glimmer of long-term hope but brings short-term challenges. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has finalized new efficiency standards for distribution transformers, a move that initially caused significant concern in the industry. The original proposal would have effectively mandated a switch from GOES to amorphous steel cores, a material for which domestic supply chains were nearly nonexistent. The final rule, however, is a compromise that allows for a longer transition period and the continued use of GOES in many applications.

This regulatory clarity is essential for unlocking investments. Manufacturers who were hesitant to retool their factories for GOES production while the threat of an undefined mandate loomed can now move forward with expansion plans. However, the domestic supply of GOES remains a bottleneck. With only one major domestic producer of this specialized steel, the U.S. market is highly vulnerable to a single-point failure. Expanding domestic electrical steel capacity is a matter of national security, yet it competes with the demand for similar steel grades used in electric vehicle motors.

Utility managers must actively engage with this domestic ecosystem. This involves not only purchasing American-made products but also participating in demand-signaling initiatives that give manufacturers the confidence to invest in capacity expansion. By aggregating demand forecasts and sharing them with domestic suppliers, the utility sector can help de-risk the substantial capital investments needed to build new transformer plants. This collaborative effort between the buyer and the manufacturer is crucial for rebuilding the industrial base.

Conclusion

The supply chain crisis facing the U.S. electric power industry is not just a temporary disruption but a fundamental reset. The combination of rapid load growth, geopolitical fragmentation, and a weakened industrial base has established a new normal characterized by scarcity, volatility, and longer lead times. For middle managers and executives, success in this environment demands a shift away from the efficiency-first principles of the past.

Resilience must now be the top key performance indicator. This involves a multifaceted strategy: diversifying supply sources through friend-shoring to reduce geopolitical risk, embracing inventory pooling and standardization to maximize asset availability, and forming long-term partnerships with suppliers to ensure capacity. It also calls for a proactive approach to domestic manufacturing, supporting the policy and industrial shifts needed to rebuild American capacity.

The way forward is costly and complicated. It calls for closer collaboration across engineering, finance, and supply chain teams. It involves tough talks with regulators about the costs of resilience and the need for higher inventory levels. But the alternative—a grid that can’t grow to meet future demands or recover from current shocks—is unthinkable. By adopting these strategic pillars, the industry can manage the current crisis and build a supply chain that’s not only efficient but also strong enough to support America’s growth in the coming century.